My first taste of Nanjing duck cuisine was amazing. The skin was crispy, the meat was tender, and it had a hint of star anise. This flavor reminded me of old recipes. Nanjing, in Jiangsu province, is known for its traditional Chinese gastronomy.

This city is often less known than Beijing or Shanghai. But it has a rich food history. Every street corner has its own story, from steamed buns to river fish cooked with local herbs. Nanjing’s food is a mix of old traditions and new flavors.

Exploring Nanjing, I found how its food connects the north and south. The smell of roasting ducks fills the air. Tea houses serve dishes that remind us of the Ming dynasty’s taste.

In Nanjing, Nanjing duck cuisine is more than just food. It’s a way to keep traditions alive and to innovate.

Key Takeaways

- Nanjing’s food scene is a mix of old traditions and new ideas, based on Jiangsu province food.

- Nanjing duck cuisine is famous worldwide but is deeply connected to local flavors.

- The city’s markets and restaurants show traditional Chinese gastronomy through dishes like tangbao and desserts with osmanthuses.

- Nanjing’s food culture respects Chinese culinary heritage, linking ancient ways to today’s tastes.

- Discovering Nanjing’s food is a chance to try flavors often missed in common Chinese food stories.

Nanjing: China’s Overlooked Culinary Gem

Walking through Nanjing’s shadowed alleys, I tasted flavors steeped in centuries of change. This city, where emperors’s palaces once stood, hides dishes that tell stories of power and tradition. Its kitchens bridge north and south, yet few outsiders know its secrets.

A Former Capital’s Food Legacy

Emperors once demanded perfection: their banquets demanded Chinese imperial cuisine that blended refinement with boldness. In a 17th-century tavern, I learned how Ming-era duck roasting techniques shape modern recipes. “Every grain of salt here remembers a dynasty,” said one chef, her hands shaping dough like ancient artisans.

The Meeting Point of North and South Chinese Cuisine

Nanjing’s riverside location forged its North-South fusion cuisine. Diners savor:

- Steamed buns with wheat-based dough stuffed with southern-style braised pork

- Stir-fried dishes using northern spices in southern wok techniques

These dishes mirror the Yangtze’s flow—uniting what divides.

Why Nanjing Deserves Culinary Recognition

Its regional Chinese cooking deserves global stages. Think of Jiangnan-style soups simmered with northern wheat pastas, or duck glazed with sauces from both culinary worlds. For explorers, this city offers more than duck: it’s a living archive of flavors. As culinary adventurers know, its kitchens redefine what Chinese cuisine can be.

The Duck Obsession: Signature Poultry Preparations

My first bite of Nanjing salted duck at a family-run stall near Confucius Street was amazing. The skin crackled and the meat was tender with a salty taste. This showed me the city’s deep love for duck.

At Master Zhou’s kitchen, I saw sixth-generation chef Li Wei show how to prepare duck. He said, “The salt must penetrate the skin three times.” He sprinkled coarse sea salt over the ducks. The whole process takes 48 hours, turning simple ducks into tender treats.

“Every grain of salt tells a story,” Zhou said, wiping sweat from his brow. “This isn’t cooking—it’s conversation with history.”

Nanjing’s duck specialties go beyond the famous salted duck:

- Crispy-skinned roasted duck glazed with local honey

- Steamed duck blood soup in earthenware pots

- Cold shredded duck salad with sesame vinaigrette

What makes these dishes special is the care put into them. Duck broth cooks for hours to make rich stocks. Even the bones are used in hearty soups. Duck is more than meat here; it connects us to the city’s history. Every meal is a journey through tradition, where each bite is a new discovery.

A Culinary Tour of Nanjing (Jiangsu Province): My Personal Journey

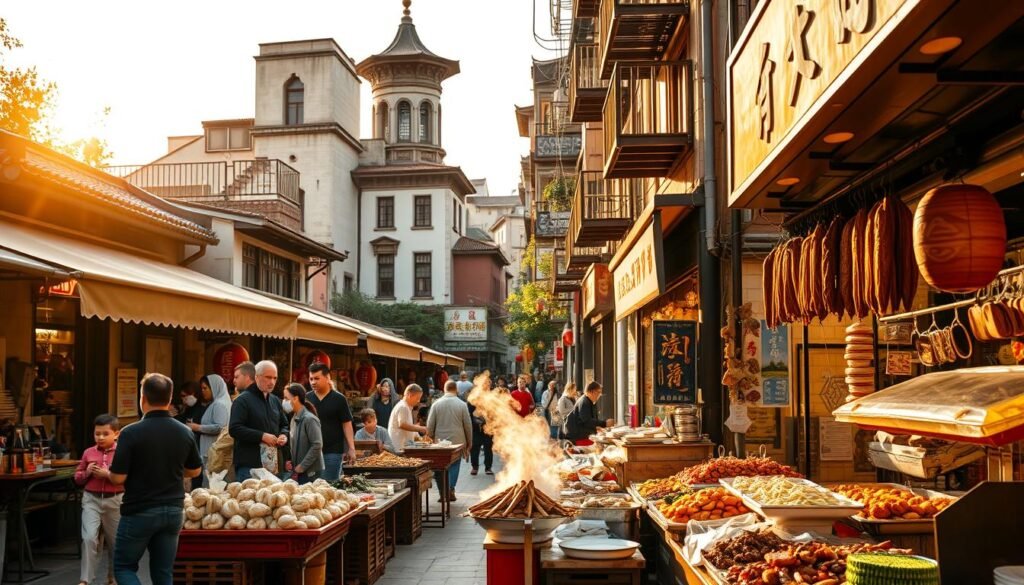

Walking through Nanjing’s alleys at dawn, I caught the sizzle of Chinese street food stalls. The air was filled with the scent of morning markets. My Nanjing culinary experiences started on the streets, where the city’s flavors are most alive.

From Street Food to Fine Dining

At 5 a.m., the jiangsu cuisine exploration begins with steamed buns full of pork and bamboo shoots. Their sesame oil glistens. By night, Michelin-starred places like Epicurean Escape serve sous-vide duck confit, reimagining classics. This shows Nanjing’s mix of tradition and innovation.

The Markets That Feed a City

- Rainbow of Jiangsu vegetables: bitter melon, lotus roots, and snow peas

- Fish stalls piled with Silver carp from the Yangtze, scales shining

- Spice racks holding century eggs and fermented bean pastes

Local Chefs and Their Passion

Master chef Zhang Wei taught me to stir-fry chaoshao pork with a wok’s rhythm. “Fire must kiss the pan,” he said, “not scorch it.” His Nanjing food tours show how dishes like duck blood soup have lasted centuries. Each spoonful connects past and present.

Beyond Duck: Surprising Flavors and Unexpected Delights

Nanjing’s duck is famous, but the city’s food scene goes far beyond it. You’ll find Chinese soup dumplings and river fish dishes. These Jiangsu province specialties mix old traditions with new ideas.

Nanjing Salted Duck: The Perfect Balance

Salted duck is more than just a dish in Nanjing. It’s a mix of salty and spicy flavors. At Master Liu’s stall, you can taste the difference.

Here, the duck is brined with Sichuan peppercorns. This method is unique to Nanjing. It’s a twist on a northern Chinese technique.

Nanjing Tangbao: Soup Dumplings That Rival Shanghai’s

The Nanjing tangbao dumplings are a work of art. Their thin skin holds a rich broth. It’s like a taste of the Yangtze River.

Chefs make each dumpling with 18 precise folds. It’s a skill that rivals calligraphy.

| Feature | Nanjing Tangbao | Shanghai Xiaolongbao |

|---|---|---|

| Filling | Pork and crab | Pork and beef |

| Broth Base | Chicken consommé | Pork bone marrow |

| Serving Style | Accompanied by black vinegar | Pairing with sesame oil |

Even those who don’t like soup dumplings will be surprised here.

River Fish: Yangtze River Cuisine Redefined

At dawn, fishermen bring in carp and bream from the Yangtze. Chef Zhang turns them into dishes like sweet and sour mandarin fish. The tamarind glaze balances the fish’s earthy taste.

A local boat captain shared a secret. He uses ginger and rice wine to purify the fish’s essence.

“The river’s flavors are purest at sunrise—they taste like the sky meeting water,” said fishmonger Mei Li.

These dishes show that freshwater cooking can be as good as oceanic dishes.

How Nanjing’s Cuisine Differs From Better-Known Chinese Food in America

When I shared sweet-and-sour carp from Nanjing with friends in New York, their eyes widened. “This isn’t what we get in Chinese cuisine in America,” one said, noticing the dish’s citrus tang. This shows how regional Chinese cooking focuses on balance, a key element lost when dishes travel.

- Flavor Nuance: Nanjing’s culinary authenticity uses fresh ingredients and complex flavors. For example, smoked duck legs have a smoky taste, unlike the soy-and-ketchup mixes found in American restaurants.

- Ingredient Integrity: Here, river fish is cooked with local ginger and scallions. In the U.S., it’s often breaded or covered in cream sauce.

- Technique Over Garnish: A chef in my favorite Jiangsu restaurant showed me how to fold Nanjing’s tangbao dumplings. They have 24 pleats to keep the broth inside, unlike the “lotus” wraps in takeout spots.

“In America, they want boldness. Here, we seek harmony,” said Chef Liang, whose family has run a restaurant for a century. “True authentic Chinese food isn’t a shortcut—it’s a conversation with the land.”

My journey showed how regional Chinese cooking adapts yet stays true. To taste Nanjing’s soul, look for markets where chefs use river-reared carp or braise pork with local rice wine. For a deeper experience, explore our culinary tours and taste the difference for yourself.

The Sweet Side of Nanjing: Desserts and Pastries Worth the Trip

Exploring Nanjing’s historic alleys, I found a world where Chinese desserts turn meals into beautiful endings. After enjoying bold flavors like braised duck, locals take you to places with Nanjing sweets. These traditional Chinese pastries are more than snacks; they’re stories in food.

Rain Flower Cakes: A Taste of Local History

In a bakery near Qinhuai River, I saw dough made into lotus shapes. They were stamped with Rain Flower Pebble patterns. These cakes, filled with lotus seed paste and sesame, taste like autumn leaves.

Their design is inspired by a Tang Dynasty poem. This shows that traditional Chinese pastries here are both art and food. They change with the seasons, like plum blossom petals in spring and chestnuts in winter.

Osmanthes Treats: Fragrant and Delicate

In fall, osmanthes desserts fill the air with their scent. Golden blossoms make jellies and sticky rice cakes fragrant. An artisan told me, “We capture autumn’s scent in every bite.”

For a similar taste, try Epicurean Escape’s zest-infused recipes. But nothing beats Nanjing’s osmanthes-infused wines at Confucius Street.

“A good dessert must be a whisper, not a shout,” said Master Li, dusting osmanthes powder on mooncakes. His words show Nanjing’s belief: Chinese desserts here are about balance and art, never overpowering but completing a meal.

These treats are more than sweets; they’re treasures. Each bite of Nanjing sweets tells a story of centuries of tradition. It shows the city’s culinary heart is as deep in sugar as in soy sauce.

Seasonal Eating: How Nanjing’s Menu Changes Throughout the Year

In Nanjing, the seasons guide what you eat. Seasonal Chinese cuisine is a long-standing tradition. It tells the story of the earth’s cycles through every bite.

From spring’s tender bamboo shoots to autumn’s buttery hairy crab roe, the city’s dishes reflect the changing world.

Spring Delicacies: Fresh and Vibrant

Spring brings green bursts to markets. Chefs make dishes like sparrow peas with bamboo shoots to celebrate renewal. They use spring ingredients in Chinese cooking.

Vendors fill baskets with wild water dropworts. These delicate stems are used in light broths. They cleanse palates after winter’s richness.

Winter Warmers: Comfort Food in the Cold Months

When it’s cold, Chinese winter foods appear. Claypot braised pork with lotus roots simmers on tables. Herbal soups with goji berries and ginseng promise health.

One winter, I joined locals sipping chrysanthemum tea. They paired it with steamed buns stuffed with preserved pork. It was a humble yet soul-warming ritual.

The Autumn Hairy Crab Phenomenon

Autumn’s highlight is the hairy crab season. Restaurants become crab temples. They offer platters with live crabs and tools for cracking their shells.

Locals debate whether female crabs’ roe or males’ meat is better. Chefs steam them with rice wine and ginger. This lets their oceanic sweetness shine.

| Season | Signature Ingredient | Must-Try Dish | Cultural Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Bamboo shoots | Wild vegetable dumplings | Symbolizes rebirth |

| Autumn | Hairy crab | Crab roe with chrysanthemum vinegar | Peak of hairy crab season |

| Winter | Lotus root | Lotus root braised pork | Body-warming tradition |

These changes are more than practical. They’re a love letter to impermanence. A plate of spring’s pea shoots or a steaming crab leg is more than food. It’s a conversation with the land itself.

The Cultural Significance Behind Nanjing’s Most Beloved Dishes

Exploring Nanjing’s markets, I found that its dishes are more than just food. They are stories of Chinese cultural heritage. The Salted Duck, for example, has a history dating back to the Ming Dynasty. It was a favorite of emperors, showing the city’s rich past.

Culinary traditions in China reflect the society’s values. In Nanjing, old and new meet in the kitchen.

A local chef once told me, “Every fold of a tangbao hides a story.”

“Our dumplings aren’t just food—they’re conversations between generations,”

an elder shared, her hands moving deftly. Even simple snacks like stir-fried water spinach with fermented tofu tell stories of survival. These dishes show the city’s resilience and pride.

Festivals in Nanjing are special. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, mooncakes symbolize family reunions. The round shape represents unity, and sharing them shows the community spirit of Chinese food culture.

Home dinners also have deep meanings. Elders are served first, and dishes are arranged to honor harmony. These customs are alive in the city’s identity.

When I helped make glutinous rice balls for Lantern Festival, it was a moment of unity. The sticky rice wrapped in bamboo leaves told stories of abundance. Eating Nanjing’s dishes is like tasting the city’s soul, which values its heritage as much as its flavors.

Conclusion: Why Nanjing Should Be Your Next Culinary Destination

Nanjing’s food scene is a mix of old stories and new tastes. Every dish tells a tale of dynasties and rivers. For culinary travel destinations, this city is more than just food—it’s a journey into China’s heart. From the crispy salted duck to the tangy tangbao, Nanjing’s food is truly unique.

Thinking of visiting? Autumn brings hairy crab feasts, and spring’s markets are alive with color. Language barriers fade as you share meals. Chefs point to steaming pots, and vendors smile when you try preserved veggies.

Foodie travel in China here means embracing the unexpected. Whether exploring spice markets or enjoying tangyuan soup in winter, Nanjing has it all. This city’s food is a bridge between past and present, visitors and locals, curiosity and belonging.

To taste Nanjing is to explore a living history. Every smell and taste tells a story. Bring your curiosity and hunger; this hidden gem is waiting for you.